Section outline

-

Jovana Blagojevic

Department of Plant Disease Institute for Plant Protection and Environment Teodora Drajzera 9, 11040 Beograd, Srbija

-

-

Urban forests are crucial component of urban ecosystems, providing essential functions such as improving air quality, regulating climate, managing water, and supporting biodiversity. These functions are vital for the health and well-being of urban populations, especially as cities continue to expand globally (1,2). At the core of these benefits is the microbiome—an invisible yet indispensable community of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms. This complex and diverse network drives key ecosystem processes like nutrient cycling, soil fertility, plant health, and decomposition, forming the foundation of urban forest health, resilience and functionality (4,7).

-

-

-

Urban forest microbiomes are very diverse and abundant, existing in soil, on tree surfaces, and even in the surrounding air and water. A single gram of soil can harbor billions of microbial cells and thousands of taxa, while the phyllosphere (the above-ground parts of the plants) can host even greater number of bacteria than comparably sized ocean or soil (2). This vast microbial diversity is not just a reflection of ecosystem health but a critical driver of ecological balance. These microorganisms stabilize soil structure, enhance nutrient and water absorption through associations like mycorrhizal fungi and nitrogen-fixing bacteria, and form protective associations with tree roots, making them less vulnerable to infection. Similarly, endophytic microbes residing within plant tissues increase tree resistance by producing bioactive compounds and improving tolerance to pollution, soil degradation, and climate-related stressors (2,3,4,5).

However, disruptions to microbial diversity—caused by pollution, urban fragmentation, or invasive species—can have cascading effects on urban forest biosecurity. For instance, disturbed microbial communities may fail to suppress pathogens which can decimate tree populations and destabilize ecosystems. Moreover, the homogenization of urban soil microbiomes, a common consequence of urbanization, reduces their ability to adapt to localized threats, increasing vulnerability to disease outbreaks and invasive species (1,5,6).

The influence of microbiome extends beyond tree health to broader urban ecosystem stability. Microbial activity in soil and phyllosphere significantly shapes urban air microbiomes, which in turn affect the spread of airborne pathogens and public health. Research has shown that diverse vegetation influence microbial richness in the air, potentially mitigating respiratory diseases and other health risks (8,9). As urbanization accelerates, understanding and preserving these vital microbial communities is essential to maintaining the services urban forests provide.

Image 1. The microbiome of forests including urban forests thrives across diverse habitats (10).

-

-

-

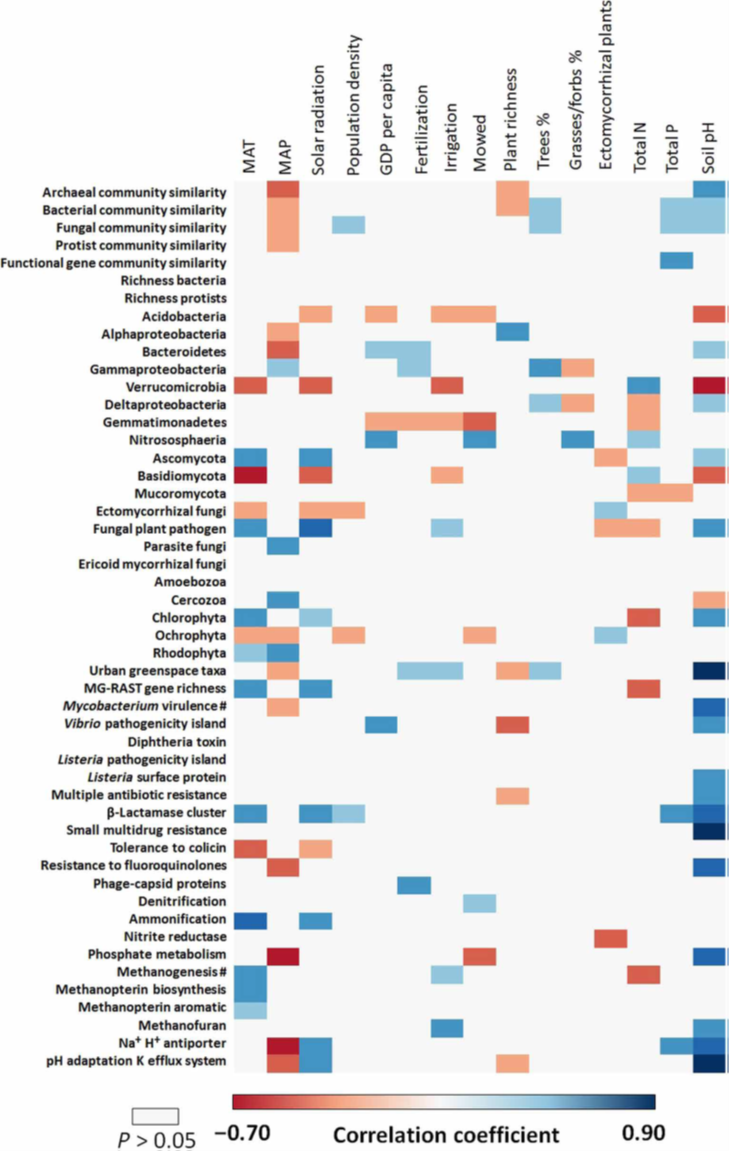

Microbial communities in urban greenspaces differ significantly from those in natural ecosystems due to unique urban pressures. While habitats like the phyllosphere and air play significant roles, soil remains the cornerstone of microbial diversity in urban forests ecosystems (7). It often favors higher proportions of fast-growing and fast-adapting taxa such are Gammaproteobacteria, Deltaproteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Gemmatimonadetes, Ascomycota, Chlorophyta, and Amoebozoa. For example, Gammaproteobacteria and Bacteroidetes in soil benefit from high nitrogen and phosphorus availability while Amoebozoa prefer frequent irrigation. Photosynthetic organisms like Chlorophyta are also common in urban soils, colonizing exposed, nutrient-rich surfaces (2,11).

Urban soils, tend to have reduced diversity of mycorrhizal fungi, crucial for nutrient exchange with plant roots, likely caused by soil disturbance, habitat fragmentation, chemical pollutants and lack of suitable host plants, which can negatively affect urban forest health (12). Additionally, urban forests harbor a higher concentration of fungal pathogens and plant parasites, including Fusarium, Pythium, and Verticillium, which can outcompete beneficial microbes in polluted and degraded areas (13). Once established, these pathogens can reduce plant growth, decrease biodiversity, and increase tree mortality. Urban trade hubs are particularly vulnerable to invasive pathogens like Phytophthora ramorum and Xylella fastidiosa, often introduced through ornamental plant movements. Without natural antagonists, these invasive species disrupt microbial communities and pose significant biosecurity risks (5,13).

Interestingly, while urban greenspaces often exhibit high local (alpha) diversity of microbial taxa such as bacteria and protists, they display reduced geographic variation (beta diversity) compared to natural ecosystems. This pattern found on 56 cities across the world underscores the global homogenizing effects of urbanization. Urban soils in cities around the world increasingly share similar microbial characteristics due to common urban pressures, reducing the capacity of microbial communities to provide location-specific ecosystem services. This homogenization makes urban forests more vulnerable to uniform stressors, such as climate change and invasive pathogens (11)

-

-

-

Urban forests face specific pressures which are not present in natural forests, that influence the structure and function of their microbiomes, reducing the health and resilience of urban forests (6).

Environmental factors

· Pollution: Urban soils often contain pollutants, such as heavy metals, nitrogen, pesticides, and chemical runoff, which can alter microbial communities by favoring certain tolerant species over others. This shift in microbial composition may reduce overall diversity, undermining soil health and the ecosystem services provided by urban forests (6).

· Soil compaction and loss of soil organic matter: Construction, foot traffic, and urban infrastructure development often lead to compacted soils, which restrict water and air flow critical for microbial survival. Compaction reduces microbial activity and diversity, limiting nutrient availability and oxygen for both plants and soil microbes, ultimately weakening urban trees over time (14). Reduced inputs of organic material from trees due to leaf removal and limited understory vegetation deplete resources for soil microbes (6).

· Urban heat islands and climate change: Cities typically experience higher temperatures than surrounding areas, a phenomenon known as the "urban heat island effect" which shifts microbial communities toward heat-tolerant species and often pathogenic species at the expense of beneficial soil fungi and bacteria As climate patterns change, pathogens may become more aggressive or better adapted to urban conditions, further complicating biosecurity efforts (2,6).

· Fragmented green spaces and hydrological changes: Unlike continuous natural forests, urban forests are often fragmented, consisting of small, isolated patches of green space which restricts the movement and distribution of microbial species, reducing overall microbial diversity and resilience. This makes the urban ecosystem less stable and more vulnerable to disease outbreaks. Urbanization alters natural water flows, leading to issues such as waterlogging or drainage problems. These changes influence aquatic and soil microbial communities, impacting nutrient cycling and ecosystem stability (6).

· Loss of tree-microbe interactions: Changes in tree composition, such as replacing native species with non-native or ornamental ones, reduce the availability of compatible hosts for specialized microbes like ectomycorrhizal fungi (2, 12).

· Disturbance and management practices: Intensive forest management practices, such as clear-cutting or frequent leaf litter removal, disrupt microbial habitats and reduce the input of organic material into the soil. These disturbances degrade soil health and impact microbial diversity and function (5).

Socioeconomic factors

· Economic development: Cities with higher per capita GDP or greater population density often face greater environmental stresses, such as industrial pollution, habitat fragmentation, and intensive urban development. Conversely, wealthier cities may also invest more in green infrastructure and urban forest management, potentially mitigating some negative effects (11).

· Green space accessibility and management: Socioeconomic disparities influence the quantity and quality of green spaces available. Low-income areas often have fewer or poorly maintained urban forests, limiting microbial diversity and associated ecosystem services. Practices such as irrigation and fertilization vary widely depending on available resources, shaping microbial communities differently across urban areas (11).

· Global trade and urbanization: Urban environments are often entry points for invasive pathogens and non-native species that compete with or harm native microbial communities. Urbanization contributes to the homogenization of microbial communities, where unique local microbes are often replaced by a more resilient, more stress-tolerant species. This microbial homogenization makes urban forests more susceptible to invasive pathogens and pests by weakling the urban forests natural defense mechanisms (6,11).

Image 2. The most important socioeconomic factors, management practices, and environmental drivers of the taxonomic and functional properties of the soil microbiome of urban greenspaces (2)

-

-

-

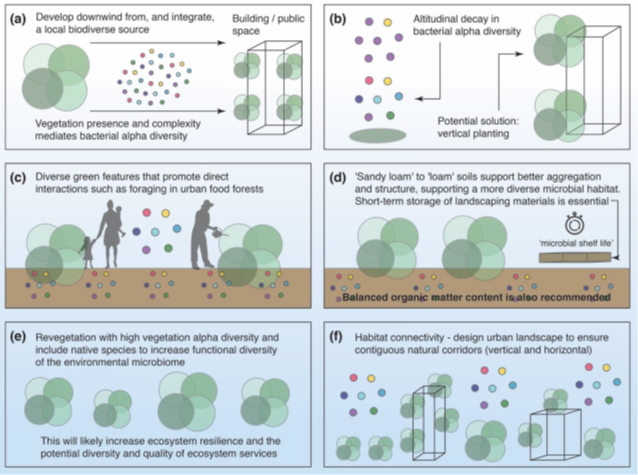

Given the biosecurity challenges faced by urban forest microbiomes, several strategies have been proposed to protect and manage these microbial communities:

· Regular monitoring: Continuous microbial monitoring helps detect biosecurity threats early, allowing city managers to respond proactively. High-throughput sequencing and microbial profiling are increasingly used to monitor soil health and detect the presence of invasive pathogens (5,6)

· Promoting beneficial microbial communities: Techniques like bioaugmentation (adding beneficial microbes to soil) and organic soil amendments can improve soil health and increase microbial diversity. For instance, introducing specific fungal species can enhance nutrient availability and boost tree resilience to environmental stressors (2,14).

· Integrated biosecurity policies: Urban planning and biosecurity policies can mitigate microbial threats. Policies might include guidelines for tree planting, such as avoiding non-native species that could harbor invasive microbes, incorporating microbiome insights into urban green infrastructure and implementing quarantine measures for imported plants. Urban-specific threats to microbiomes require specific strategies such as designing green corridors to enhance connectivity between fragmented urban forests. Coordinated efforts between public health officials, urban planners, and environmental scientists are crucial (2,14).

· Community engagement and education: Public involvement is key to successful biosecurity in urban forests. Programs to educate residents about the importance of avoiding soil or plant material movement can reduce the spread of invasive species. Citizen science initiatives involving the public in monitoring tree and soil health are also gaining popularity (2,14).

Image 3. Key strategies for enhancing urban microbiomes, including vegetation complexity, habitat connectivity, biodiverse revegetation, and soil management to promote ecosystem and microbial health (14).

-

-

-

One of the recent most promising approaches in enhancing urban forest resilience is about exploring synthetic microbial communities to combat stressors like pollution and soil degradation, improving plant health and ecosystem function. Research on heat-tolerant microbes offers adaptive strategies to support urban trees in changing climates (2). Key challenges include understanding pathogen dynamics and their interactions with urban microbiomes to mitigate disease outbreaks and the spread of invasive species. Monitoring climate-driven microbial shifts is essential to maintain microbial balance and prevent adverse impacts on urban ecosystems (2,14). Focusing on these priorities will enable sustainable strategies to strengthen urban forest health and resilience.

-

-

-

1. Wan, X., Zhou, R., Yuan, Y., Xing, W., & Liu, S. (2024). Microbiota associated with urban forests. PeerJ, 12, e16987. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.16987

2. Brüssow, F., Brüessow, F., & Brüssow, H. (2024). The role of the plant microbiome for forestry, agriculture, and urban greenspace in times of environmental change. Microbial Biotechnology, 17(e14482). https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.14482

3. Pavithra, G., Bindal, S., Rana, M., & Srivastava, S. (2020). Role of Endophytic Microbes Against Plant Pathogens: A Review. Asian Journal of Plant Sciences, 19(1), 47-55. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajps.2020.47.55

4. Trivedi, P., Leach, J. E., Tringe, S. G., Saeed, S., & Singh, B. K. (2020). Plant–microbiome interactions: from community assembly to plant health. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 18(11), 607–621. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0412-1

5. Nazli, F., Khan, M. Y., Jamil, M., Nadeem, S. M., & Ahmad, M. (2020). Soil microbes and plant health. In Plant Disease Management Strategies for Sustainable Agriculture Through Traditional and Modern Approaches (pp. 111-135). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35955-3_6

6. Rosier, C. L., Polson, S. W., D’Amico III, V., Kan, J., & Trammell, T. L. E. (2021). Urbanization pressures alter tree rhizosphere microbiomes. Scientific Reports, 11, 9447. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88839-8

7. King, G. M. (2014). Urban microbiomes and urban ecology: how do microbes in the built environment affect human sustainability in cities? Journal of Microbiology, 52(9), 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12275-014-4364-x

8. Li, H., Wu, Z.-F., Yang, X.-R., An, X.-L., Ren, Y., & Su, J.-Q. (2021). Urban greenness and plant species are key factors in shaping air microbiomes and reducing airborne pathogens. Environment International, 153, 106539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106539

9. Lymperopoulou, D. S., Adams, R. I., & Lindow, S. E. (2016). Contribution of vegetation to the microbial composition of nearby outdoor air. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 82(13), 3822–3833. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00610-16

10. Baldrian, P. (2017). Forest microbiome: diversity, complexity and dynamics. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 41(2), 109-130. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuw040

11. Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Eldridge, D. J., Liu, Y.-R., Sokoya, B., Wang, J.-T., Hu, H.-W., He, J.-Z., et al. (2021). Global homogenization of the structure and function in the soil microbiome of urban greenspaces. Science Advances, 7, eabg5809. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abg5809

12. Scholier, T., Lavrinienko, A., Hindstroem, R., et al. (2021). The impact of urbanization on soil microbial community diversity and functionality. Microbial Ecology and Ecosystem Function, 56(3), 445-459. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16754

13. Cacciola, S. O., & Gullino, M. L. (2019). Emerging and re-emerging fungus and oomycete soil-borne plant diseases in Italy. Phytopathologia Mediterranea, 58(3), 451-472. https://doi.org/10.14601/Phyto-10756

14. Robinson, J. M., Watkins, H., Man, I., et al. (2021). Microbiome-inspired green infrastructure: A bioscience roadmap for urban ecosystem health. Architectural Research Quarterly, 25(4), 292-303. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1359135522000148

-

-