Section outline

-

Urban forests face specific pressures which are not present in natural forests, that influence the structure and function of their microbiomes, reducing the health and resilience of urban forests (6).

Environmental factors

· Pollution: Urban soils often contain pollutants, such as heavy metals, nitrogen, pesticides, and chemical runoff, which can alter microbial communities by favoring certain tolerant species over others. This shift in microbial composition may reduce overall diversity, undermining soil health and the ecosystem services provided by urban forests (6).

· Soil compaction and loss of soil organic matter: Construction, foot traffic, and urban infrastructure development often lead to compacted soils, which restrict water and air flow critical for microbial survival. Compaction reduces microbial activity and diversity, limiting nutrient availability and oxygen for both plants and soil microbes, ultimately weakening urban trees over time (14). Reduced inputs of organic material from trees due to leaf removal and limited understory vegetation deplete resources for soil microbes (6).

· Urban heat islands and climate change: Cities typically experience higher temperatures than surrounding areas, a phenomenon known as the "urban heat island effect" which shifts microbial communities toward heat-tolerant species and often pathogenic species at the expense of beneficial soil fungi and bacteria As climate patterns change, pathogens may become more aggressive or better adapted to urban conditions, further complicating biosecurity efforts (2,6).

· Fragmented green spaces and hydrological changes: Unlike continuous natural forests, urban forests are often fragmented, consisting of small, isolated patches of green space which restricts the movement and distribution of microbial species, reducing overall microbial diversity and resilience. This makes the urban ecosystem less stable and more vulnerable to disease outbreaks. Urbanization alters natural water flows, leading to issues such as waterlogging or drainage problems. These changes influence aquatic and soil microbial communities, impacting nutrient cycling and ecosystem stability (6).

· Loss of tree-microbe interactions: Changes in tree composition, such as replacing native species with non-native or ornamental ones, reduce the availability of compatible hosts for specialized microbes like ectomycorrhizal fungi (2, 12).

· Disturbance and management practices: Intensive forest management practices, such as clear-cutting or frequent leaf litter removal, disrupt microbial habitats and reduce the input of organic material into the soil. These disturbances degrade soil health and impact microbial diversity and function (5).

Socioeconomic factors

· Economic development: Cities with higher per capita GDP or greater population density often face greater environmental stresses, such as industrial pollution, habitat fragmentation, and intensive urban development. Conversely, wealthier cities may also invest more in green infrastructure and urban forest management, potentially mitigating some negative effects (11).

· Green space accessibility and management: Socioeconomic disparities influence the quantity and quality of green spaces available. Low-income areas often have fewer or poorly maintained urban forests, limiting microbial diversity and associated ecosystem services. Practices such as irrigation and fertilization vary widely depending on available resources, shaping microbial communities differently across urban areas (11).

· Global trade and urbanization: Urban environments are often entry points for invasive pathogens and non-native species that compete with or harm native microbial communities. Urbanization contributes to the homogenization of microbial communities, where unique local microbes are often replaced by a more resilient, more stress-tolerant species. This microbial homogenization makes urban forests more susceptible to invasive pathogens and pests by weakling the urban forests natural defense mechanisms (6,11).

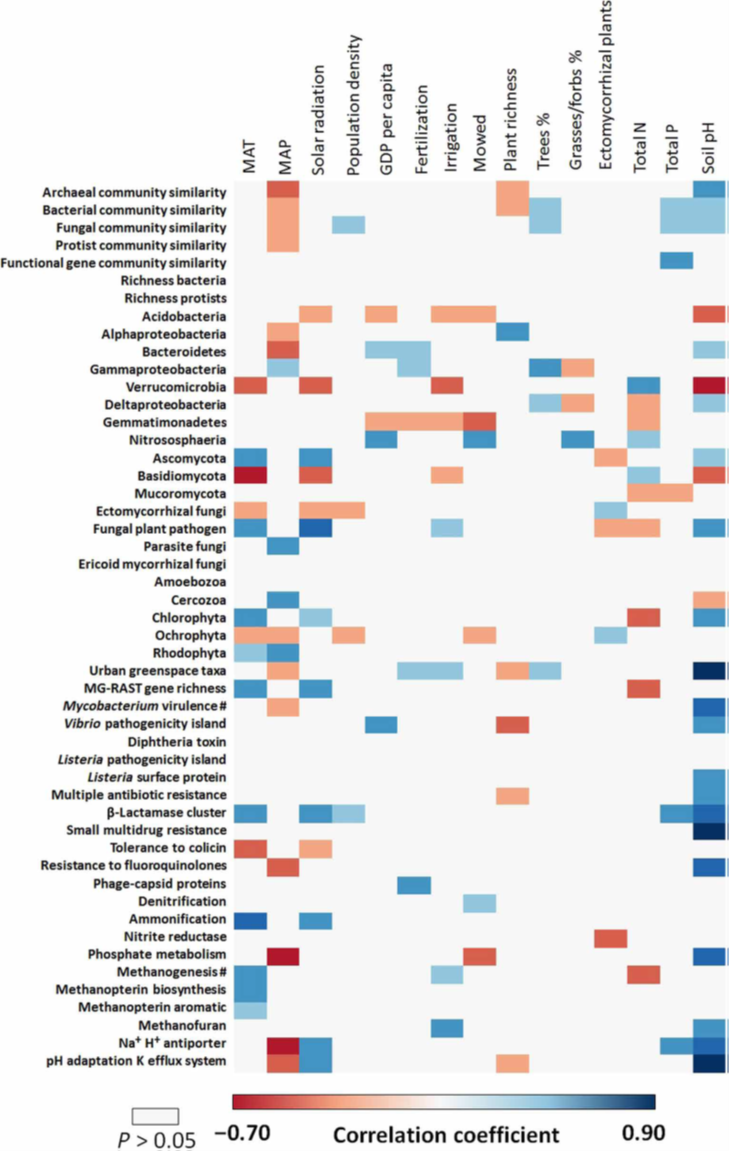

Image 2. The most important socioeconomic factors, management practices, and environmental drivers of the taxonomic and functional properties of the soil microbiome of urban greenspaces (2)