Section outline

-

Jovana Blagojevic

Department of Plant Disease Institute for Plant Protection and Environment Teodora Drajzera 9, 11040 Beograd, Srbija

-

-

Urbanization has led to significant economic and social benefits, but as many recent studies suggested, also brought chronic health conditions linked to urban living. While cities have been increasingly associated with high prevalence of diseases such as asthma, allergies, autoimmune disorders, and inflammatory conditions, all linked to immune system dysfunction - urban forests, described as the lungs of cities, emerge as a important resource not only for environmental health but also for human well-being. Far more than just the trees, they are dynamic ecosystems filled with life, including invisible yet vitally important microbial communities. These microbiomes thriving in soil, air, leaves and water are an integral part of the larger urban microbiome, having a vital role in supporting ecosystem balance and human health. As cities expand and ecosystems face pressures from urbanization, understanding the urban forest microbiomes and their impact to environmental and human well-being is essential (4,14,12).

-

-

-

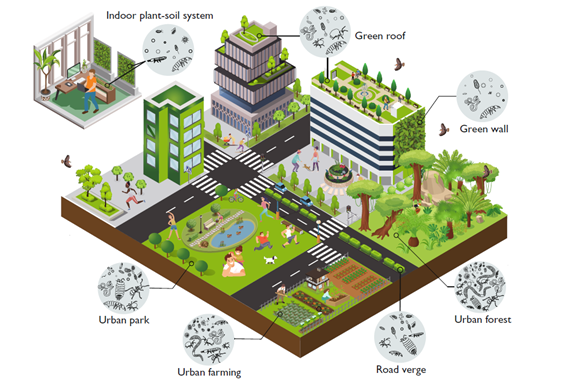

Urban forest microbiomes are dynamic and interconnected systems, interacting across multiple interfaces, including the soil zone, rhizosphere, phyllosphere, plant-atmosphere (5). These microbiomes are shaped by urbanization factors such as pollution, habitat fragmentation, disrupted soil chemistry, and reduced biodiversity, which differentiate them from natural forest systems. Despite, these diverse microbial communities support vital ecosystem functions, including nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, pollutant breakdown, and plant resilience (1,9). Key component of urban forest microbiomes (5):

· Soil microbiomes: Urban forest soils host microorganisms essential for nutrient cycling, pollutant breakdown, and organic matter decomposition. These processes support soil fertility, vegetation growth, and ecosystem health, but urban soil compaction and pollution can disrupt microbial dynamics (14,10,9).

· Rhizosphere: The rhizosphere, the zone surrounding tree roots, is a microbial hotspot where mycorrhizal fungi and bacteria enhance nutrient absorption and plant resilience against drought and pathogens (14). Tree species play a critical role in defining rhizosphere microbiomes, forming species-specific associations with fungi that influence nutrient cycling and tree health. Root exudates and litter chemistry further shape microbial diversity, emphasizing the importance of tree diversity in maintaining robust rhizosphere communities (7). Soil management practices, like excessive fertilization, can disrupt these symbiotic relationships (8,14).

· Decaying wood and leaf litter: Decomposing organic matter provides nutrients to the soil, supports microbial diversity, and enhances carbon storage in urban ecosystems. However, urban practices like litter removal may reduce these ecological benefits (1,9).

· Phyllosphere: The phyllosphere—the aerial surfaces of trees, including leaves and bark—harbors microbial communities that play a key role in nutrient cycling, plant health, and air quality. These microbes can suppress foliar pathogens, regulate the exchange of gases, and contribute to pollutant degradation. Urban environmental stressors, such as pollution and temperature fluctuations, can influence the composition of phyllosphere microbiomes, potentially impacting their beneficial functions (5).

-

-

-

Urban forest microbiomes interact with human health in multiple pathways, including airborne transmission, water systems, urban infrastructure interactions, direct contact with trees, and additional soil-mediated processes (6,9).

· Airborne pathways

The microbial communities in the air ,"aerobiome ", play a vital role in urban forest ecosystems and human health. Urban forests influence the diversity of the aerobiome by releasing microbial propagules from their canopies, which interact with airborne populations and settle on urban surfaces. This microbial exchange contributes to improved air quality and reduced atmospheric pollutants (5). The composition of the aerobiome varies with land use, influenced by the balance between vegetation and urban infrastructure (6). Epiphytic microbes on plant surfaces also contribute significantly to the aerobiome, enriching it with beneficial species that support ecosystem health (14).

· Water Pathways

Urban forest microbiomes play a crucial role in maintaining water quality and hydrological balance acting as natural filters, breaking down harmful pollutants such as hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and excess nutrients in stormwater, to supports cleaner water systems and reduces contamination risks (10,2). Additionally, the use of treated wastewater for irrigation enriches soil microbial diversity, fostering tree health and enhancing ecosystem resilience. These beneficial microbes improve nutrient cycling and pollutant degradation, contributing to urban forest vitality (11,12). However, irrigation practices with untreated or poorly treated wastewater can introduce harmful pathogens, antibiotic-resistant genes, and chemical pollutants into forest soils, posing significant threats to both public health and ecosystem stability (10,2).

· Urban infrastructure

Urban infrastructure, including buildings and sewage systems, directly interacts with urban forest microbiomes, shaping their composition and functions. Microbial propagules from forest canopies settle on urban surfaces, enhancing microbial diversity (6). Conversely, building runoff introduces pollutants or new microbial species into forest soils, potentially disrupting their balance (10,12). Sewage systems can also influence urban forest microbiomes. Properly treated wastewater supports soil microbial diversity and tree health, enhancing ecosystem services like air purification and carbon sequestration. However, poorly managed sewage risks introducing pathogens, compromising both forest and human health (10).

· Direct contact with urban forests

The phyllosphere serves as a direct link between humans and urban forest microbiomes. During recreational or work activities in urban forests, humans come into contact with these microbial communities. Beneficial microbes from the phyllosphere can strengthen skin immunity and reduce allergic reactions, but in some cases, fungal spores or pathogenic bacteria on leaf surfaces can trigger infections or allergies in sensitive individuals (6,7,2).

Image 1. Urban microbiomes interact across soil, rhizosphere, phyllosphere, plant-atmosphere, infrastructure interfaces, supporting critical ecosystem functions despite urbanization impacts (12).

-

-

-

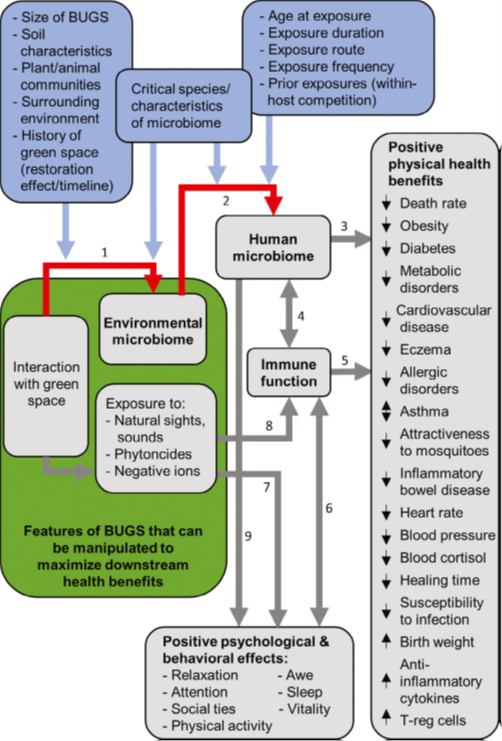

The microbiomes in urban forests influence human health in direct and indirect ways (2). From immune system modulation to mental health benefits, these interactions underscore the necessity of preserving and enhancing urban forest microbiomes (7,9).

Positive impact on human health

· Immune system regulation and support.

Exposure to diverse environmental microbes from urban forests helps training the human immune system to differentiate between harmful and harmless agents (12). Studies have revealed that exposure to biodiverse forests soil can reduce urban associated chronic disease such as asthma, allergies and inflammatory diseases. Specific microbes, such as Mycobacterium vaccae, have been linked to immune regulation and even mood enhancement (2,7).

· Enhancing gut microbiota

Contact with soil and forest environments influences the composition of the human gut microbiome. Healthy urban forest soils harbor beneficial microbes that can colonize the human gut, promoting metabolic health and reducing inflammation (7, 12).

· Mental health and psychological well-being

Time spent in urban forests has been shown to reduce stress and anxiety, improve mood, and promote cognition. Part of these benefits can be attributed to interactions with microbial communities that influence neurobiological responses, such as the release of serotonin-modulating compounds (8,4).

· Pathogen suppression and detoxification

The microbiomes in forest soils can degrade harmful organic pollutants, such as pesticides and hydrocarbons, and suppresses soil-borne pathogens. This reduces the potential for contamination in urban water supplies and minimizes exposure to harmful elements (5, 12).

Image 2. Studies emphasize the potential of biodiverse green spaces (BUGS) to alleviate urban health challenges by exposing people to a diverse array of environmental microorganisms, enhancing immune system regulation and reducing chronic inflammatory diseases. BUGS*- Biodiverse urban green spaces (4)

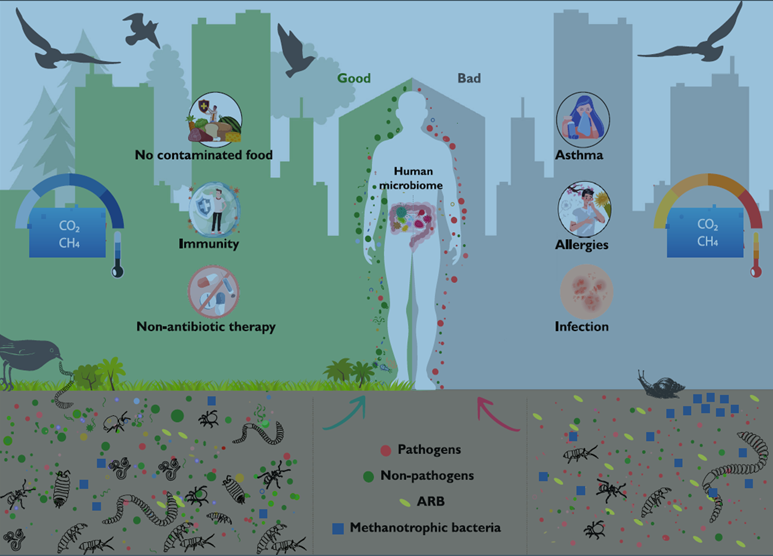

Negative impact on human health Pathogenic threats

Urban forests can harbor pathogens such as fungal spores, zoonotic bacteria, and viruses. These pathogens may spread to humans and animals, leading to health issues ranging from respiratory problems to zoonotic diseases (12).

· Antibiotic resistance

Urban soils often act as reservoirs for antibiotic-resistant genes due to pollutants, including untreated wastewater and industrial runoff. These resistance genes can spread through human-environment interactions, exacerbating public health concerns (11,10)

· Interaction with pollutants

Urban microbiomes frequently interact with pollutants such as heavy metals, hydrocarbons, and pesticides. While some microbes can degrade these pollutants, others may produce harmful by-products, negatively impacting soil health and human safety (7,12)

· Allergic reactions and immune overload

Although exposure to diverse microbes generally supports immune health, certain microbial populations in urban forests may trigger allergic reactions or hypersensitivity in some individuals. High concentrations of fungal spores or pollen can exacerbate asthma and hay fever, especially in cities with reduced biodiversity (8, 12, 9).

-

-

-

Preserving and enhancing the microbiomes of urban forests can maximize their benefits for human health.

· Biodiverse green space design

Incorporating native plants and minimizing soil sealing can protect microbial habitats. Green roofs, urban parks, and reforestation projects provide opportunities to restore microbial diversity (9).

· Pollution mitigation strategies

Reducing pollutants through waste management and bioremediation supports the detoxification functions of forest microbiomes. This creates a safer environment for both urban ecosystems and their human populations (9,12).

· Community engagement and citizen science

Educating communities about the importance of urban forest microbiomes fosters public support for conservation. Citizen science projects that monitor soil and tree health can directly involve urban populations in preserving forest microbiomes (7).

· Integration in urban planning

Urban planning that prioritizes connectivity between forest patches, reduces fragmentation, and incorporates green corridors can enhance microbial exchange and diversity across urban forests (7,12).

Image 3. Microbial diversity supports urban health by enhancing soil health, suppressing pathogens, reducing pollutants, and boosting human immunity and microbiome regulation (12).

-

-

-

Urban forests are vital for fostering microbial diversity and ecological health in cities. Their microbiomes offer direct and indirect health benefits, from boosting immune resilience to reducing pollution exposure. However, these systems are fragile and require intentional conservation efforts. By prioritizing urban forest microbiomes in city planning and public health strategies, it can create healthier, more sustainable urban environments that benefit both nature and humanity.

-

-

-

1. Baldrian, P. (2017). Forest microbiome: diversity, complexity and dynamics. FEMS Microbiology reviews, 41(2), 109-130 https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuw040

2. Brevik, E. C., Slaughter, L., Singh, B. R., Steffan, J. J., Collier, D., Barnhart, P., & Pereira, P. (2020). Soil and human health: current status and future needs. Air, Soil and Water Research, 13, 1178622120934441. https://doi.org/10.1201/b13683-4

3. Flies, E. J., Mavoa, S., Zosky, G. R., Mantzioris, E., Williams, C., Eri, R., Brook, B. W., Buettel, J. C. (2019). Urban-associated diseases: Candidate diseases, environmental risk factors, and a path forward. Environment International, 138, 105187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105187

4. Flies, E. J., Skelly, C., Negi, S. S., Prabhakaran, P., Liu, Q., Liu, K., ... & Weinstein, P. (2017). Biodiverse green spaces: a prescription for global urban health. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 15(9), 510-516 https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1630

5. Gandolfi, I., Canedoli, C., Rosatelli, A., Covino, S., Cappelletti, D., Sebastiani, B., ... & Franzetti, A. (2024). Microbiomes of urban trees: unveiling contributions to atmospheric pollution mitigation. Frontiers in Microbiology, 15, 1470376. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1470376

6. King, G. M. (2014). Urban microbiomes and urban ecology: how do microbes in the built environment affect human sustainability in cities? Journal of Microbiology, 52(9), 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12275-014-4364-x

7. Monaco, P., Baldoni, A., Naclerio, G., Scippa, G. S., & Bucci, A. (2024). Impact of Plant–Microbe Interactions with a Focus on Poorly Investigated Urban Ecosystems—A Review. Microorganisms, 12(7), 1276. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12071276

8. Nowak, David J. 2020. Urban trees, air quality and human health. In: Gallis, Christos; Shin, Won Sop, eds. Forests for public health. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing: 31-55.

9. Nugent, A., & Allison, S. D. (2022). A framework for soil microbial ecology in urban ecosystems. Ecosphere, 13(3), e3968. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3968

10. Roguet, A., Newton, R. J., Eren, A. M., & McLellan, S. L. (2022). Guts of the urban ecosystem: microbial ecology of sewer infrastructure. Msystems, 7(4), e00118-22. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00118-22

11. Steffan, J. J., Brevik, E. C., Burgess, L. C., & Cerdà, A. (2018). The effect of soil on human health: an overview. European journal of soil science, 69(1), 159-171. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12451

12. Sun, X., Liddicoat, C., Tiunov, A., Wang, B., Zhang, Y., Lu, C., ... & Zhu, Y. G. (2023). Harnessing soil biodiversity to promote human health in cities. npj Urban sustainability, 3(1), 5. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s42949-023-00086-0

13. Urbanová, M., Šnajdr, J., & Baldrian, P. (2015). Composition of fungal and bacterial communities in forest litter and soil is largely determined by dominant trees. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 84, 53-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.02.011

14. Wan, X., Zhou, R., Yuan, Y., Xing, W., & Liu, S. (2024). Microbiota associated with urban forests. PeerJ, 12, e16987. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.16987

-

-