Urban Tree Management for the Sustainable Development of Green Cities

This book provides a comprehensive overview of the role, management, and significance of urban trees in creating sustainable green cities. It explores the ecological, social, psychological, and economic benefits of trees, while also addressing the challenges of maintaining them in urban environments. Topics include tree biology, stress adaptation, pathology, risk assessment, pruning, transplantation, and maintenance practices. The book also examines broader issues such as biodiversity, invasive species, governance, and community involvement in urban forestry. Through contributions from leading experts, it combines scientific research with practical strategies to ensure that trees continue to enhance urban life, health, and resilience in the face of climate change and urbanization.

1. Intro: Urban trees – Importance, benefits, problems

1.1 Introduction

Trees often and quickly gain a bad reputation, caused by falling branches or entire trees, roots in sewage drains, neighbors fighting over fruit and leaves littering their gardens, health issues from pollen allergies, etc. The problems caused by city trees are usually more conspicuous and have greater ramifications. Their advantages can often be difficult to record and to assess. As a result, the negative impacts are much more widely discussed, whereas extensive papers about their positive aspects are rare. This chapter, therefore, aims to raise awareness of the positive impacts and benefits of urban trees and their importance to city dwellers (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). It describes their advantages (with no claim to completeness) and details their effects on our quality of life and well‐being – aspects that are increasingly important in these times of progressing urbanization.

“If I knew the world would end tomorrow, I would still plant another tree today.”

– Martin Luther

1.2 aesthetics, sensory impressions

To many people, the beauty of nature is manifest in trees (Tyrväinen et al., 2005). This is especially true for ancient, free‐standing trees. Their variation in phenology (change of appearance across the seasons), including shooting, blooming, fruit, leaf coloring and falling leaves, is an important factor in how we experience the seasons, especially in cities. Many trees even change their smell over the course of the year. Areas without trees can be areas without seasons, especially in temperate climates. Visual impressions such as coloring (e.g., of the leaves in spring and autumn), different structures (e.g., the shape of the leaves and the architecture of the treetops), design (e.g., Lombardy poplars, ancient oaks) and aesthetics (how a tree affects us) cause positive emotions and experiences (Bahamón, 2008; Miller, 2007; Trowbridge and Bassuk, 2004; Smardon, 1988; Velarde et al., 2007). As an example of the aesthetic impact of different tree species, just think of a light, young grove of birches, as opposed to a dark, dense forest of conifers in spring. An assessment based on aesthetics is, of course, subjective, but it may still be used, for example, to rank city trees by popularity. Aside from visual impressions, the senses of smell (blossoms, autumn leaves), hearing (rustling of the treetops, rustling of the fallen leaves), taste (fruit, young leaves) and touch (fruit, young leaves) also play important roles.

1.3 psychology, well‐being, health

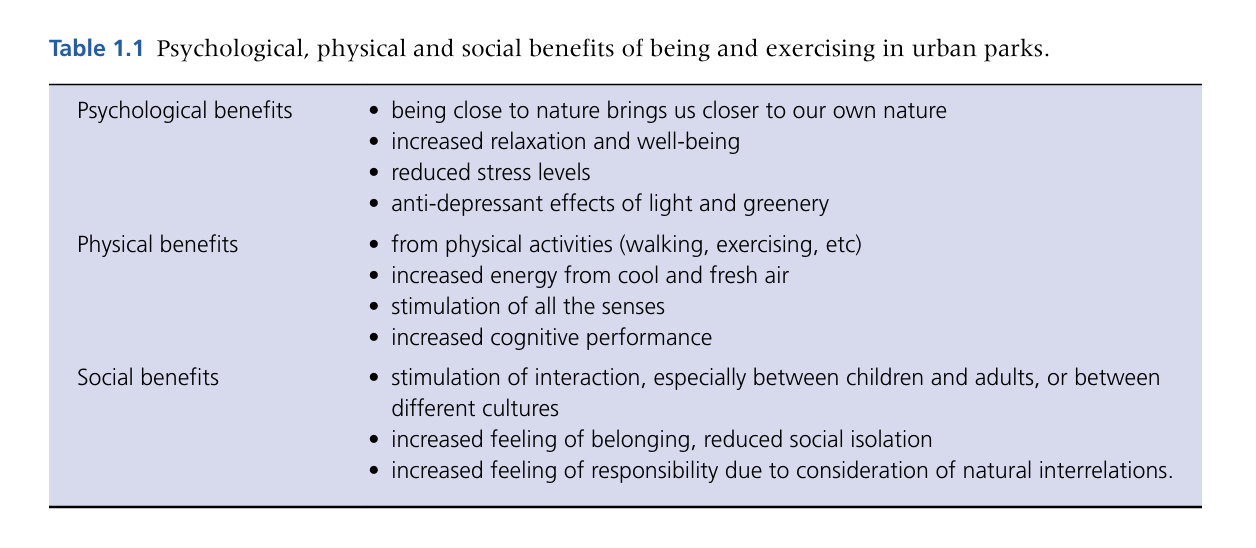

Trees accompany us through life. Relationships between trees and people are complex and have been poorly investigated. The potential of such relationships becomes clear if you consider the “house tree”. Even today, it is not uncommon for families to plant a tree next to their home – for example, to serve as a “patron”, in order to have shade in summer and shelter from wind, or in order to grow fruit, honey, and so on (Figure 1.3). Some house trees are even considered a member of the family, and the bond is particularly strong if the tree was planted by the owner of the home to mark a special occasion. Positive feelings towards house trees are usually associated with aesthetics: “looks nice”; “the blossoms”; “the color of the leaves”. Gardens often contain many of the “public” trees along the streets and in the parks of a city. In Dresden, for example, there are 600,000 private garden trees, but only 60,000 public street trees (Roloff, 2013). Trees are also increasingly important for our health – for instance, visits to parks (municipal, spas and civic parks) and gardens, walks and hikes, resting on a bench under a tree, picnics in the shade of trees (a popular custom in many cultures). Parks may therefore also be called “therapeutic landscapes”, and a movement called “garden therapy” is currently on the rise. Gardens (including allotments) are increasingly seen as personal spas, as a place where people can feel comfortable and relax – gardening as private health care. In addition, city trees also protect us from emissions, especially by reducing the levels of ozone, nitrogen oxides, sulfur and carbon dioxide (Harris et al., 2004; Konijnendijk et al., 2005; Tyrväinen et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2005; Donovan et al., 2011). Parks act as a city’s “green lungs”. In recent years there have been many discussions about particulate matter and how it can be reduced to protect our health, with a focus on the ability of trees to bind microparticles in their leaves. Benefits from this depend on factors such as the placement of the trees along the streets, and the width of the streets (see Chapter 13). Due to their positive impact on our psyche and health (Harris et al., 2004; Konijnendijk et al., 2005; Tyrväinen et al., 2005; Arnberger, 2006; Hansmann et al., 2007; Carreiro et al., 2008; Konijnendijk, 2008; Miller, 2007; Velarde et al., 2007; Cox, 2011; Lee and Maheswaran, 2011), and because they have been proven to accelerate recovery and regeneration, trees often dominate the parks that belong to spas, asylums, or hospitals, as well as cemeteries. They also provide the shade needed in summer, they reduce noise and improve the quality of the air, and they have a calming effect on the mind (see Figure 1.4) (Harris et al., 2004; Tyrväinen et al., 2005). Parks are also popular places for physical activities (ball games, walking, running, etc. – Lohr et al., 2004; Matsuoka and Kaplan, 2008). Recent research shows the importance of nature for the living environment and local recreation; nature is seen as the most important factor. The physical, psychological and social benefits of being and exercising in green areas (e.g., in parks and gardens) are summarized in Table 1.1. Trees can also have a lasting influence in childhood, for instance by forming a local identity; a tree species that dominated our surroundings in childhood is usually associated with fond memories, and we may love it for life. Tree adoptions are a popular gift, and usually result in a personal relationship between the presentee and the tree or the tree species. Planting a birth tree at the birth of a child used to be common practice (and is becoming popular again). In the 18th century, many places had a law that a wedding license would only be granted if a certain number of young, verdant wedding trees had been planted. Wedding avenues and dummy trees (to help children wean off their pacifiers – see Figure 1.5) are examples of modern customs associated with trees. In past times, dance and court trees used to be very important. Dance lindens had a platform in the crown where dances were held; court lindens were used for meetings dedicated to law and order. The finding of justice was based on the belief that nobody would dare lie under a Tilia tree. Maypoles are tall, pruned and decorated trees that are raised as part of a festive celebration in a central place in the town. A roofing ceremony is a celebration under a tree that is attached to the roof when the shell of the building has been completed (Figure 1.6). Trees are also central in landscaping, such as in the planning and construction of parks, squares, private and landscaped gardens. A park that resembles a savannah (Figure 1.7) is particularly beneficial for humans. It accommodates our primal urge for keeping everything in sight, which originates from the prehistoric development of humankind in the African savannah. Looking at trees and shrubs gives us pleasure. Trees can create a certain ambiance (e.g., potted palm trees for a tropical flair). The psychological aspects of the relationship between people and trees are particularly noticeable in tree‐based horoscopes (e.g., the “Celtic tree horoscope”). These use certain tree types, depending on their appearance (e.g., Quercus for toughness, Pinus for pickiness, Salix for melancholia). Because ancient, giant specimens have always awed humans, trees also play an important role in mythology. Trees are the most suitable image to represent humanity, because they, too, stand tall and raise their “arms” toward heaven (“Trees are like brothers”). Many religious scriptures have tree allegories, and many sayings also use the simile of tree and human, e.g., “a bad tree does not yield good apples” or “the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree”. Many places have sacred woods.

Aspects of ancient religions often revolve around trees, such as the “tree of forbidden knowledge” at the beginning of the Bible, when Adam and Eve are expelled from Paradise after eating its fruit. Other examples are the giant ash Yggdrasil in Norse religion, or Buddha’s Tree of Enlightenment. Even today, the symbolic and spiritual importance of trees can be deduced from the coins of many countries that show trees or leaves. Songs, literature, poetry and fairy tales often revolve around trees. Many ancient stories tell of people who are turned into trees. Last, but not least, there are trees that are very special. In Germany there is one that is very special for relationships – an old Quercus tree, close to the village Eutin (north of Hamburg), called the “Flirt tree”. It is the only tree in Germany that has its own postal address and its own “letterbox” (a hole in the trunk; Figure 1.8) – exempt from the sanctity of mail. People write to the tree about their wish for a partner, husband or wife, or read and respond to the letters left in the tree by others. Aging in trees is usually seen as something positive; the older a tree, the bigger the impression it makes. Ancient trees represent birth and decline, give us a feeling of timelessness and connect us with past eras (Luther’s Tilia, Goethe’s Gingko, Newton’s apple tree – Stokes and Rodger, 2004). At the same time, they make us aware of the modest role and lifespan of the individual person. Trees create an atmosphere of piece and quiet, thus helping us to relax and improving our moods. City dwellers in Michigan, USA, said in a survey that trees are the strongest contributing factor for the attractiveness of streets and districts (Figure 1.9), whereas their absence was the most negative factor: “Streets without trees have no face.”